In doing work with mixtures of very different contaminants, managing their intricacies can be a challenge. I needed to create a system in which I could quantify the amount of a metal that was bound to a plastic versus the amount of metal that was in the water versus the amount of metal being taken up by a fish. Seems simple enough- put plastic and metal and a fish in the same place at the same time. Then take out the fish, fish out the plastics (get it? haha), and measure the metal in each compartment.

This plan works until you consider that (1) the plastic particles I was working with were 1 micron – there is no “fishing” of things that are 1 micron; and (2) the fish eat the plastics. As with every problem, I crafted what should have been a simple solution…theoretically: come up with a barrier that lets the metal move freely but that separates the fish and the plastics.

The simplicity was lost the moment I began to consider what material this barrier should be made out of. Recall it is 2023 at this point – we are in a world where most things are plastic, and what do metals like to stick to? Plastic. The entire theory behind the experiment in the first place. With plastic (and therefore what felt like 90% of the options) out of the question, I turned to other materials. The most obvious question was: how did I separate plastics and metals before? The answer was nitrocellulose filter paper.

While I am pretty crafty, I have my limits…turning a flat, circular sheet of nitrocellulose into something that can hold microplastics when suspended in the water column alongside a fish is not a crafting skill in my toolbox. However, through the power of conversations over coffee, I knew of another student who knew how to do origami. I recruited her skill and suddenly there was a cube of nitrocellulose in front of me rather than a flat sheet. Problem solved…or so I thought.

My problem identification skills were short-sighted. Not only did I need a barrier to separate plastics from fish, I needed a barrier that would remain stable for the duration of the experiment. I very quickly learned that nitrocellulose would soak up water, unfold, and generally fall apart. Back to the drawing board. I needed a barrier that was inert to not absorb metals, that would allow metal to move freely but separate plastic from fish in a tank, AND that was durable. Where might one look for such a unicorn? A scientific catalogue, of course…

After hours of searching, I found it – FIBERGLASS THIMBLES. I saved the original photo I took in fear that the numerous catalogue tabs of my browser would spontaneously shut down (as they sometimes do).

The photo was timestamped 3:38am, so how I landed in whatever chemistry corner of that catalogue that these replacement thimbles are, we will never know. I don’t think I have ever pressed “Add to Cart” and “Checkout” quite so fast.

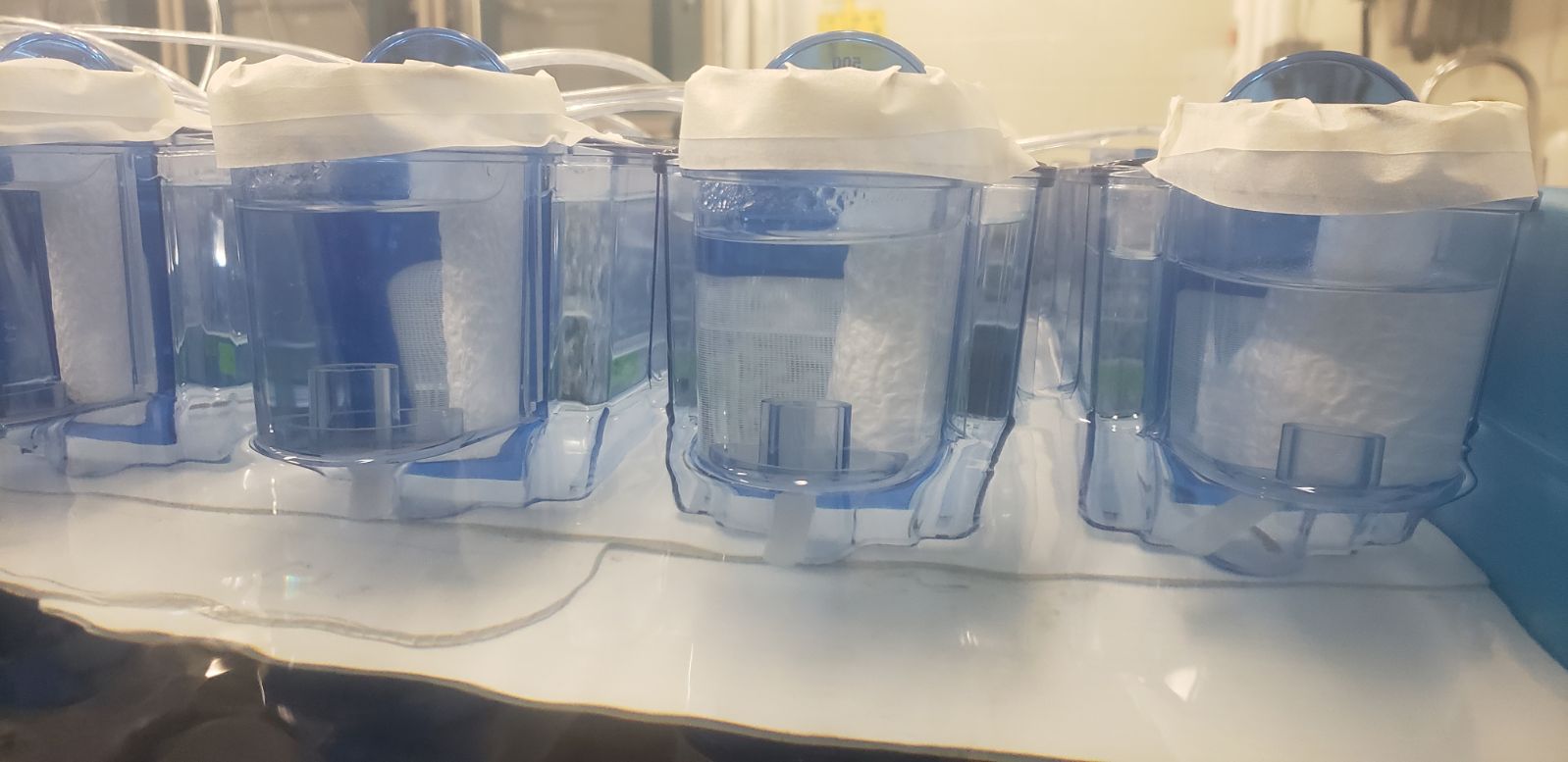

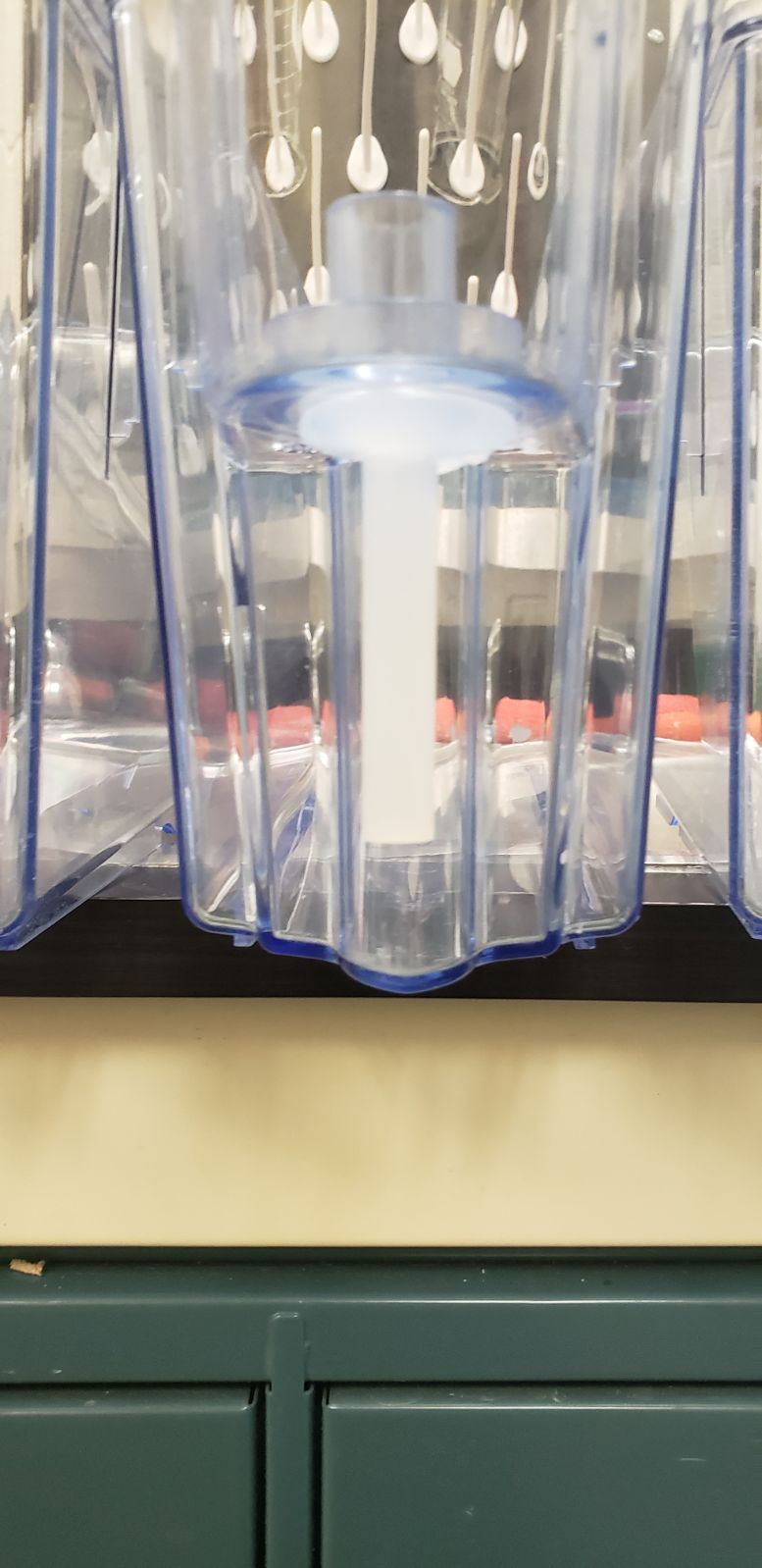

When the thimbles arrived to campus, the first challenge was quickly apparent – they float…sideways, such that the opening at the top spills all of the plastics into the water. So, we tied them up through the holes in the tank lid to suspend each thimble with none other than trusty fishing line (a must have in every lab, in my opinion).

Just when I thought I had this experimental design solidified, I was quickly humbled by none other than my species of choice, the fathead minnow. Fathead minnows are known for their resiliency, their durability, and their adaptability. What fails to be mentioned in scientific articles praising this species is that they are also the toddlers of the fish world. They try to eat EVERYTHING…including fiberglass thimbles.

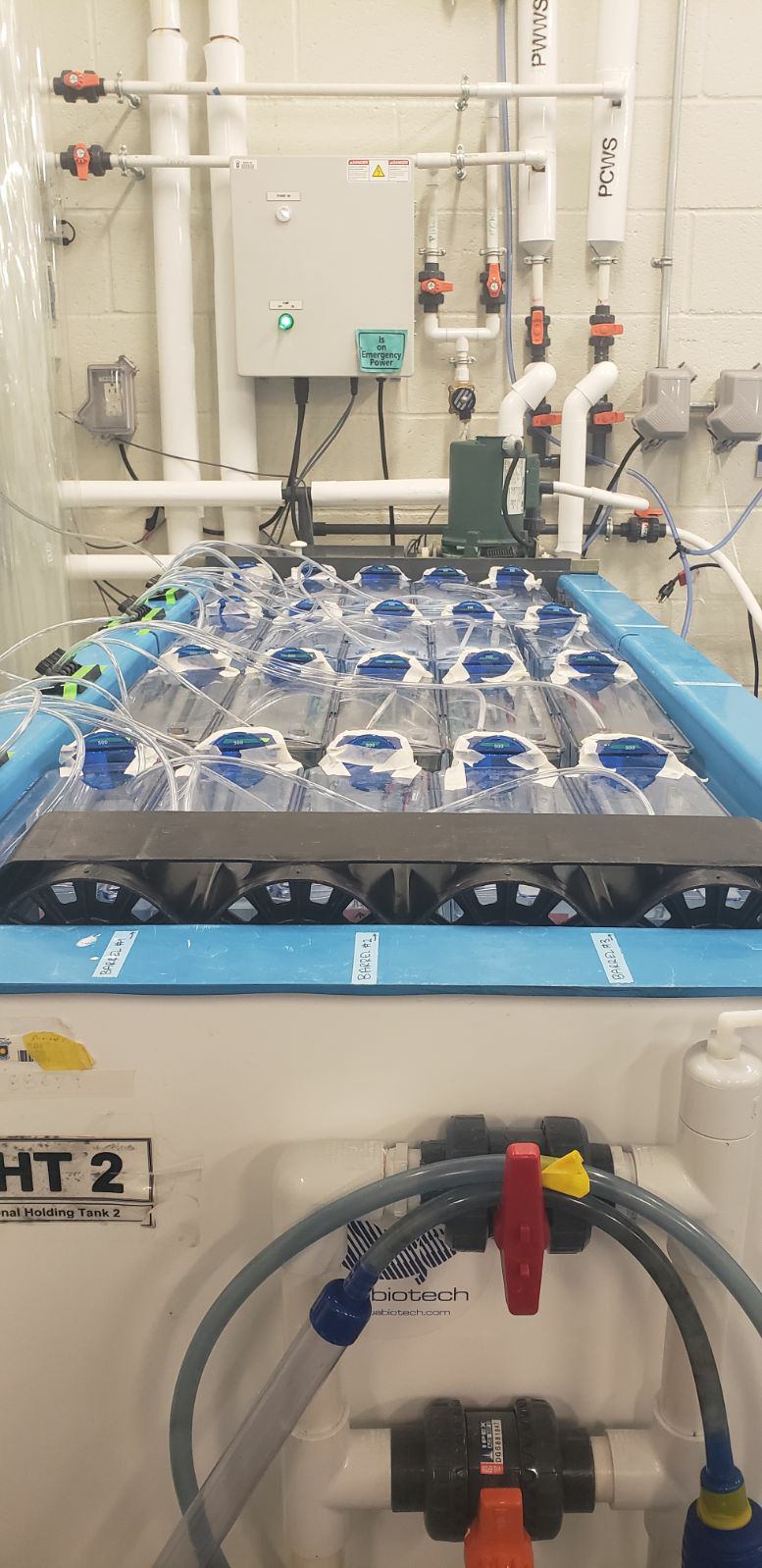

The problem took on what would end up being its final layer: I needed a barrier that was inert to not absorb metals, that would allow metal to move freely but separate plastic from fish in a tank, that was durable, AND that the fish could not eat. There’s no catalogue search function for that, so I approached from a different angle and modified the tank instead. A little bit of hot glue, some mesh barriers, and a whole lot of tape later we had the final, functional design.

While the scientific diagram of this tank design is buried in the supplemental information of the article detailing the outcome of this study – it does not quite capture the artistic nature that this innovation took.